India is going shopping for hydrocarbons. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, faced with the world's fastest growth in oil consumption, has sought deals and alliances in Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates to help secure supplies of a commodity that accounts for about a third of India's imports. On Thursday he was in Mozambique, where state-controlled Oil & Natural Gas Corp., or ONGC, has a multi-billion dollar stake in the Rovuma offshore gas field.

The sense of urgency is understandable. India will become the world's third-largest auto market by 2020, and it simply doesn't have domestic reserves capable of filling all those tanks.

But if Modi takes a look out the front of New Delhi's presidential offices to the distant smudge of the memorial arch at the other end of the city's ceremonial axis, he might ponder whether he's going after the wrong fuel.

Modi's capital was the world's most polluted major city, according to a 2014 World Health Organization analysis. While it slipped to a less choking 11th place in the WHO's most recent study this year, half of the world's 40 most polluted cities are still in India, compared with seven in China.

Struggling for Breath

India had six out of the ten most polluted cities in the world in 2014

Note: Shows annual mean concentrations of PM2.5 particulates in micrograms per cubic meter. Cities shown are top ten plus Beijing, Shanghai, New York, London and Vancouver.

The number of annual deaths attributable to air pollution rose 12 percent to almost 700,000 in 2010 from 2005, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, while the cost to India's economy from those deaths alone was equivalent to about $500 billion. And the country's car boom is only just beginning.

If only there was a way to allow the wealthier Indians of the near future to hit the roads without being asphyxiated, and chip away at that dependence on imported crude at the same time.

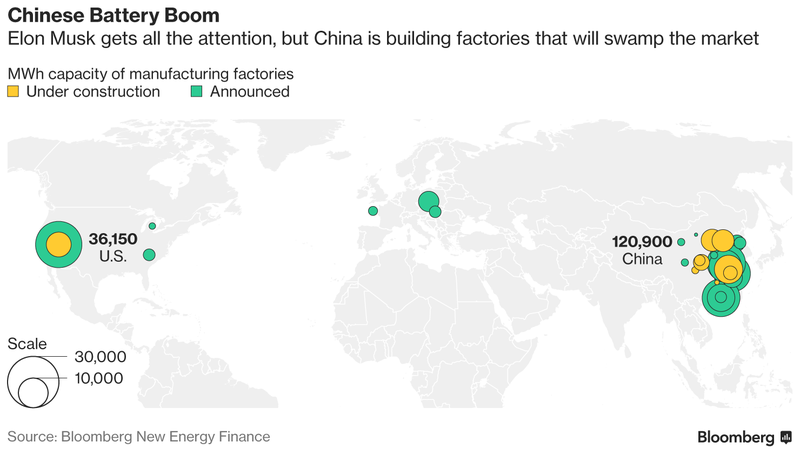

Luckily, there is. Modi visited Tesla's Silicon Valley factory last September, where he talked to founder Elon Musk about the potential for solar panels and battery storage to provide rural electrification. He should be thinking about how Tesla's technology could help the country's cities, too.

@GangsOfGtown Given high local demand, a Gigafactory in India would probably make sense in the long term.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) October 25, 2015

Prices for electric vehicles in India are already well below what you'd pay for a Model S: Mahindra's E20, a minicar that can carry four tightly packed adults for 120 kilometers on a single charge, costs about 660,000 rupees ($9,800) in Delhi. Piyush Goyal, the energy minister, earlier this year suggested the country's vehicle fleet could become 100 percent electric by 2030 by offering zero-downpayment finance to buyers, according to the New Indian Express.

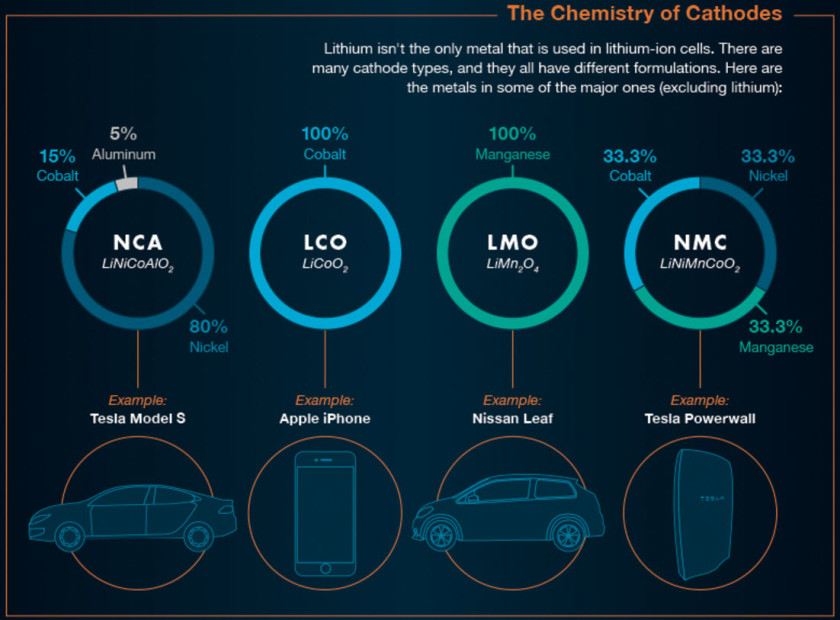

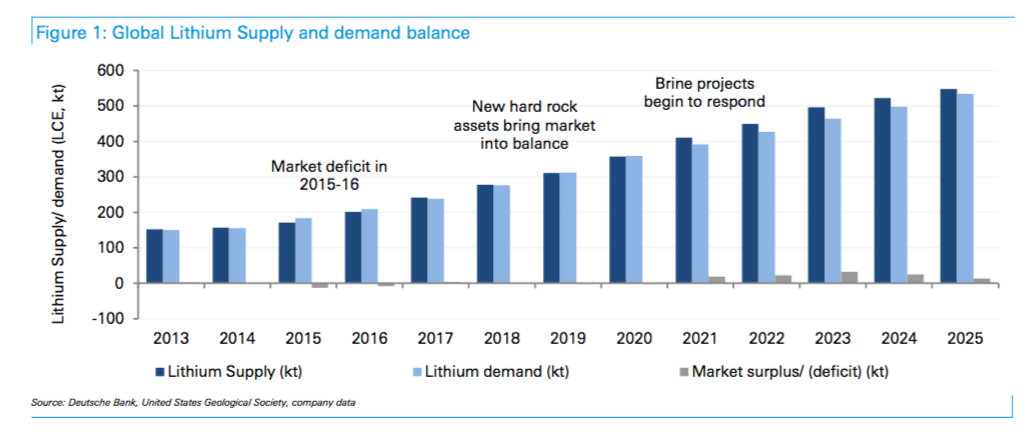

Instead of scratching the earth for another oilfield, ONGC should be tasked with finding the raw materials to help meet this target. About 80 percent of the world's resources of lithium -- an essential element in rechargeable batteries -- are locked up in just nine deposits in the Andes, the U.S., China and the Democratic Republic of Congo, according to a 2011 study.

Power Packs

About 80 percent of the world's biggest lithium resources are locked up in these nine deposits

While that suggests a tough market to break into, capital and technology can open a lot of doors. French oil major Total is spending $1.1 billion buying battery-maker Saft and Korean steelmaker Posco has even bought its way into an Argentine lithium project thanks to a new extraction process it's developing.

Quite apart from health, there are sound macroeconomic reasons for India to switch to electricity. The country's domestic reserves of lithium are if anything less significant than its oil endowment (though it's the second-biggest producer of graphite, an equally essential raw material for rechargeable batteries). But an electric car uses that metal only when it's manufactured, whereas a conventional one drinks oil year-in, year-out.

What sort of difference could a switch to electric vehicles make to India's import demand? It's not hard to come up with a rough comparison. Americans drive 13,476 miles a year on average, according to the Federal Highway Administration. At typical fuel efficiency levels of 33 miles per gallon a U.S. car will use about 6,125 gallons of gasoline over a 15-year working life -- something like $8,400 of gas at current, rather subdued, prices.

An electric minicar such as China's Mahindra-lookalike Zotye Zhidou E20 contains about 18 kilograms of lithium carbonate equivalent, according to Citigroup. At last year's lithium price of $6,800 a metric ton, that's about $122.

Spread across sales of 5 million new cars a year, that difference could be hugely significant for India's commodity-hungry economy. Oil already accounts for as much as 60 percent of the country's trade deficit, subtracting as much as 9 percent from gross domestic product, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers -- and it's only going to get worse as the country's car population grows.

Assuming domestic generation capacity can be found to charge all those batteries, India has much to gain from a switch away from gasoline. Its economy, as well as its population, would be much healthier.

Source: bloomberg.com

China's CATL to supply car batteries to Nissan and Renault